When we think of crisis and emergency we tend to conjure images of food aid, refugee camps and medical tents. Issues such as education, employment opportunities and gender equality are traditionally associated with longer-term reconstruction efforts. Yet it is precisely during the upheaval of conflict and crisis that a window of opportunity presents itself to set new socioeconomic precedents. Education is a critical entry point to harness this period of transition to promote positive change by instilling principles of gender equality.

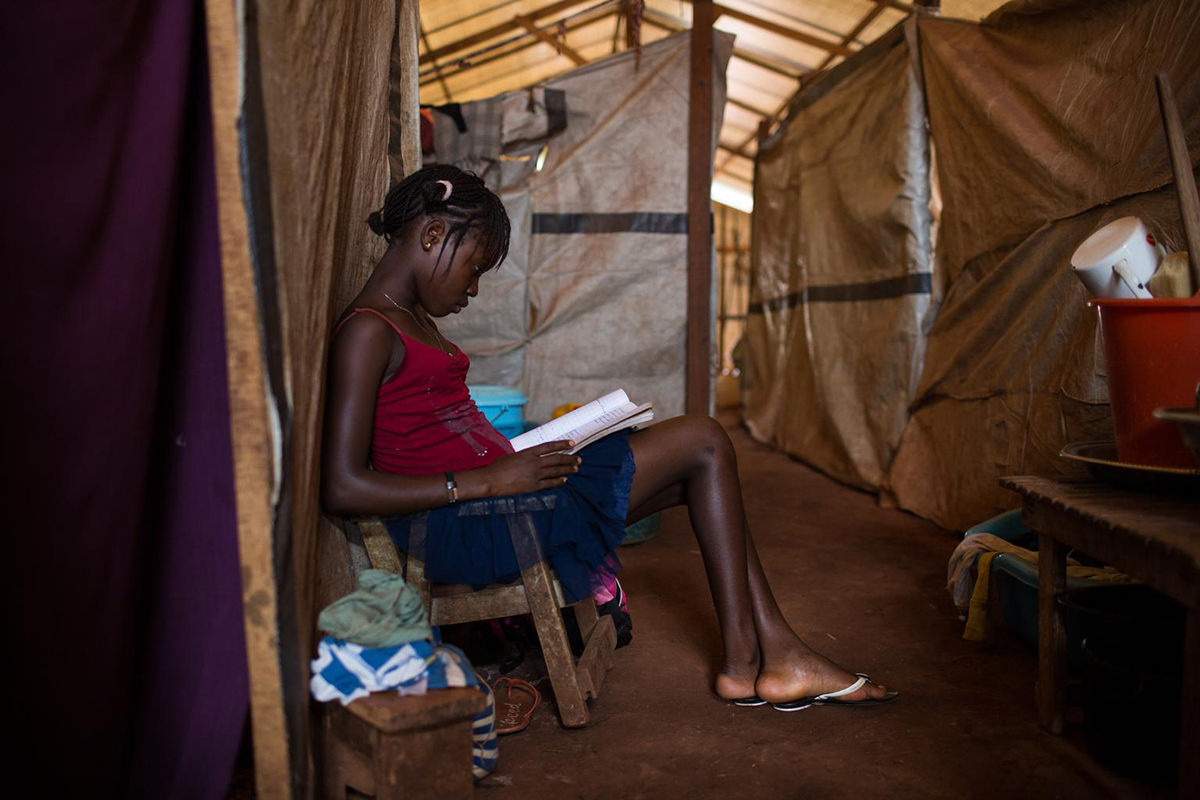

Applying a longer-term and transformative approach to education interventions immediately following crisis would enhance prospects for girls to attend school and learn safe and supportive environments. With this comes the potential to unlock the benefits of quality education in terms of health, well-being, empowerment and employment for women and girls, their children and society. Yet with girls more likely to be out of school than boys in crisis contexts, gender issues clearly need to be addressed to realise the promise of education.

Gender issues in conflict and crisis

Entrenched gender inequalities generally mean that even prior to a crisis, women and girls have less access to financial resources, social capital and legal means to protect themselves. As a result, women and girls are more vulnerable to sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), early marriage, forced prostitution and labour. This situation is particularly grave for the most marginalised girls, such as those with disabilities or from ethnic minority communities. During times of crisis, the already disproportionate burden of unpaid care work invariably falls to women and girls, as does additional household and income-generating activities. However, such social upheaval means women and girls are engaging in non-traditional activities which — if harnessed correctly — can present new opportunities for social and economic participation.

Men and boys are also uniquely affected by conflict and crisis. Boys can be more vulnerable to forced recruitment into armed groups or mobilisation into armed forces rather than attending school. Heightened poverty and insecurity also brings challenges for men and boys to fulfil traditional expectations of masculinity as ‘protectors’ and ‘providers’. Such sociocultural expectations can result in men and boys resorting to crime and violence (including SGBV) as a means of survival and reasserting power. These dynamics can perpetuate a cycle of violence and poverty — with negative repercussions for both boys’ and girls’ education.

The different ways in which girls and boys are affected by conflict and crisis can have an impact on the accessibility, safety and quality of education, with girls usually experiencing greater disadvantage. Ensuring education opportunities are available equitably, are of good quality and responsive to gender and conflict considerations will effect the best possible prospects for promoting gender equality as a key requisite for a county’s sustainable recovery.

What are the key gender and education issues in conflict and crisis settings?

Access to education

Direct threats to access routes often disproportionately affect girls. For example, destruction alongside displacement can increase distances to school, and the associated risks can lead to families prioritising their girls’ safety over their education. School buildings can also lack adequate sanitation and hygiene facilities, which poses a major barrier for menstruating girls.

Social exclusion and discriminatory norms that disadvantage women and girls often become pronounced in crisis. Insecure environments usually have elevated levels of early marriage and pregnancy which directly affect girls’ ability to complete or re-enter education. Increased upfront and hidden costs of education can also disadvantage girls. Unlike boys, education is not generally seen as an investment for girls and they are therefore usually the first to miss out in times of economic strain.

Safety in and around school

Heightened insecurity during conflict and crisis is central to the range of barriers to education experienced by both boys and girls. The use of schools for military purposes, as recruitment grounds for armed groups, the presence of soldiers, incidences of abduction and direct attacks or crossfire affect all children. However, girls’ attendance tends to be affected the most as parents are reluctant to expose them to such risks. This is further compounded by the threat and reality of targeted attacks on schoolgirls and girls’ schools. Safety and learning are also compromised by increased levels of school-related gender-based violence (SRGBV) where institutions may lack the infrastructure to create or support gender-specific policies around child protection.

Quality of education

While the general destruction of school infrastructure, limited availability of trained teachers and inappropriate teaching materials common to conflict and crisis settings can undermine the quality of education for all children, there are also specific gender implications. Available teachers are less likely to be trained in gender-sensitive approaches and existing teaching practices and learning materials can reinforce gender stereotypes that significantly disadvantage girls. Furthermore, a limited number of either female or male teachers can result in a lack of role models, and students may become less motivated to participate in class.

How should girls’ education in emergencies be addressed?

To be effective, efforts to support girls’ education should not be limited to the traditional ‘check box’ approach of simply ‘adding women and girls’. Strategies must address the different barriers that girls and boys face to obtaining a safe and quality education that are specific to individual contexts. At the same time, schools can contribute to shaping boys’ and girls’ understanding of gender roles and responsibilities to promote positive social change and gender equality.

UNGEI’s recent policy note, ‘Addressing threats to girls’ education in contexts affected by armed conflict’ offers recommendations based on successful approaches and evidence-based learning. There is an urgent need for further research on what works to advance girls’ education in conflict and crisis settings. Nonetheless, emerging evidence suggests that the following approaches can accelerate long term progress:

- Community engagement is critical for the delivery of gender-sensitive and contextually relevant education.

- Financial and in-kind support helps families to send girls to school, especially in contexts where boys’ education is prioritised.

- Targeted strategies to address SRGBV must be integrated into education programmes.

- Alternative education mechanisms are crucial where existing school systems do not provide the flexibility needed to support learners.

UNGEI and partners are highlighting the need to integrate gender issues into the education in emergencies agenda, bridging the gap between humanitarian response and longer-term development efforts. The rights, needs and concerns of all societal groups must be reflected to ensure a sustainable recovery process. To this end, education can serve as a critical tool to ensure that women and girls are not left behind. This includes promoting principles of gender equality as well as equipping girls with the necessary skills and competencies to contribute productively to a country’s recovery through economic participation and civic engagement. We now call upon global leaders to make a commitment to address gender issues in education during times of crisis as a fundamental tenet of recovery, peace and stability.