Who’d be a teacher?

You’re standing in front a class of more than a hundred children, alone and unprepared. Some pupils look at you expectantly, hopefully. Others are fighting, chatting, unfocused, even sleeping. There are bright minds here, but to nurture and motivate them is going to be an uphill struggle.

Your training did not ready you for this. It did not teach you how to discipline without corporal punishment. It did not prepare you to support children with disabilities. It did not show you how to make children fall in love with learning, with reading and writing. Frustrated with the conditions, or juggling other priorities, many of your colleagues are frequently absent.

You desperately want these pupils to do well. The low achievement in the class threatens to dishearten you, but you wouldn’t keep coming back to this low-paid job if you didn’t believe in them.

You know there are doctors in this class, lawyers, surgeons, journalists, artists and teachers. They deserve a teacher who is going to keep trying for them — and that’s what you’re going to do.

What is it really like to be a teacher?

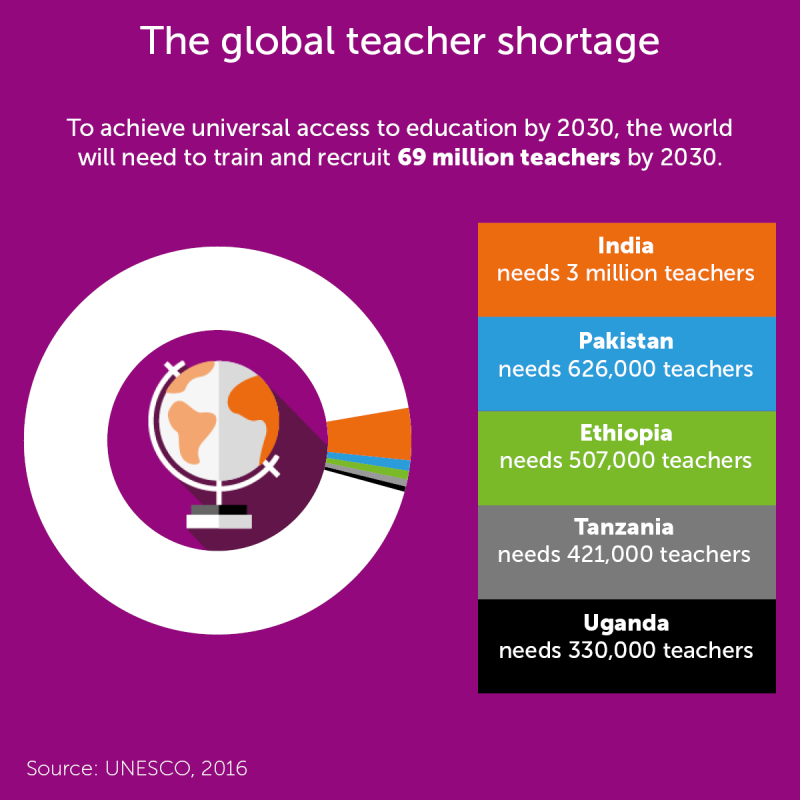

Millions of children around the world are missing out on a good quality education. To put that right, as the world has committed to doing by 2030, the world will need 69 million more teachers. The majority of them will be hired to replace the millions of teachers who are leaving the profession every year.

Why are we haemorrhaging teachers at a time we’ve never needed them more? We know that many teachers around the world are struggling, and that it is having a serious impact on the quality of education available in their classrooms.

In developing countries, teachers are telling us that they are unmotivated. They feel underqualified, disrespected, underpaid and underprepared.

“A surgeon is a respected professional in almost any country you could visit. One of the reasons is that they go through rigorous training and must master skills to a recognised standard before they can start to work. Sadly, the same in not true of teachers.” says Purna Kumar Shrestha, VSO’s lead education adviser.

“Teaching may be viewed as a stopgap on the way to something better. Low wages, poor conditions, piecemeal training and prospects mean that teacher training does not always attract the academically brightest and best students. Those that do, don’t tend to stay long.”

“Sometimes I don’t understand the activities myself”

Increasing efforts are being made to improve the provision of preschool education in Cambodia, as in many other countries. It’s seen as crucial to improving results at primary level. But it’s also piling further pressure on teachers.

VSO’s latest research in Cambodia showed that more than half of preschool teachers surveyed had zero training in early childhood pedagogy. In fact, among the preschool teachers in our survey about one in five had never progressed beyond Grade 8 education themselves (about 13+ years of age, or around Year 9 in the UK). Unsurprisingly, teachers tell us they feel inadequately trained, and unprepared to deliver quality or inclusion in their classrooms.

Chiv Koemuoyth started work as an untrained preschool teacher in her home province of Battambang after the local government called for volunteers to help plug the shortage. Since then, she’s received three months of in-service training and is now paid, but she still lacks confidence.

“Some activities and lessons I don’t understand myself, so I have to skip. When I don’t know the lesson I note it down, so I can ask when we have the technical working group [local preschool teachers’] meeting.

“The new pre-school director is from a primary school, so she doesn’t understand the support needed for preschool teachers and she isn’t able to help.”

Working conditions

The primary enrolment rate leapt from 83% to 91% worldwide between 2000 and 2015. But as millions of extra children filed into classrooms, the recruitment of teachers did not match the swelling number of pupils. The result is that class sizes have ballooned in many countries.

In Rwanda, each teacher has an average of 58 pupils to a class, while in Malawi they grapple with an average of 70. That’s in comparison to a UK average of just 17 pupils per teacher.

But these pupil: teacher ratios are averages that hide the extremes. Factoring in private education of richer, emerging middle classes, it is common for government schools in countries like Malawi to have classes of 100, even 150 pupils.

“I know that every child is not receiving the best education”

Grace Chigwechokha, 41, stands before a class of 84 children at Chiuzimbi Primary School in Malawi. Some of the faces she knows particularly well: repetition rates are so high that ages in this group range from six to 14 years old.

“To progress to the next grade, they have to get at least 50% of the marks on the end of year exam. Last time only 49 out of 84 got enough questions right to continue.

“It’s a tough job. The children all have different abilities. Being the only teacher in the class is a very big problem, because I can’t give every child individual help.

“I am trying my best. But I know that not every child is receiving the best education — I don’t feel good about that.”

Haemorrhaging teachers

It is little wonder that millions of teachers are leaving the profession every year. Having taught for over 20 years, Grace has never had a promotion or a pay rise. Nor has she had any ongoing training, apart from that accessed through VSO.

“Of course I would like to be promoted and earn more. But I would need to complete my education to degree-level first. The fees are 350,000 Kwacha (£364).

“I have children of my own. As I am trying to do what’s best for my children, I decided it is better to focus on their education and stop mine.”

A crisis in classrooms

The latest data shows that half a billion children worldwide are unable to read or do maths at the most basic level — despite two thirds of them being in school.

It’s a mind-boggling waste of human potential. We need more teachers who are better equipped to deliver a quality education in their classrooms. Teachers with ingenuity and ideas to create a learning environment out of almost nothing. Teachers who feel motivated and committed to their profession, instead of viewing it as a stop-gap.

Josephine Nyirampuhwe, 28, is one of those teachers. Every morning, Josephine walks from the small house she shares with her chronically ill aunt, flanked by a wave of exuberant four to six-year-olds.

These preschool pupils are helping Josephine carry teaching and learning materials, the majority of which she has made herself out of discarded items she finds around Bori village, in a remote southwest corner of Rwanda.

“I like thinking of things I can make for the children,” smiles Josephine. “Some bottle tops can be a counting game. A rice sack can become the costume for a moto driver. The button helps develop fine motor skills, and the role play helps introduce concepts of counting and money.”

Before she received training from VSO volunteers, Josephine had no formal education to be a teacher. She was nominated by local parents to teach children who could not afford to travel to the nearest pre-primary school, who she receives each day in a wooden building with a mud floor.

“I keep going because I have a passion for teaching”

“Those that are well-to-do take their children to better schools,” admits Josephine. “It is very difficult. Every parent should pay 500RWF per month. But when it is the end of the month, it is very possible that only one parent has brought this money.”

“Each month I earn 12,000RWF [£12] at most. It’s not enough because I don’t have money to buy shoes. But I keep going because I have passion for teaching. This is a noble position.”

Rwanda is upgrading the quality of early childhood education in hopes of reducing rates of repetition at primary school.

A new training curriculum for teachers like Josephine, developed with the support of VSO is currently being embedded across Rwanda with the help of volunteers.

No child left behind

We know that not all children experience education in the same way. Girls, children with disabilities and children from minority ethnic groups can experience further discrimination in and outside the classroom. Without specialist training, teachers cannot meet their needs and can even contribute to their exclusion.

A landmark survey conducted by VSO and the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology in Kenya, revealed 16% of all children with a disability are out of school. Those that are lack adequate support: less than 1% of special educational needs teachers had any form of training in catering for children with multiple disabilities.

Isabella Kituyi, 39, is one of those teachers. For years she scraped by at Kimwanga Special School for the Hearing Impaired in Bungoma County, Kenya, without any specialist training in meeting the needs of the children.

“On my first day, I looked at the pupils and I questioned myself: Will I manage? And if I don’t, what will I do then? What if I lose my job? I had nothing in my head to prepare me for this work, no training or knowledge of Kenyan Sign Language.”

Since being trained by VSO volunteers, Isabella is now far better able to communicate with her students — the majority of whose parents couldn’t even sign with them before our project.

“I am not giving up on these children, no matter what”

Isabella understands the huge influence a teacher can have, not just on the lives of their pupils, but on the attitudes of the communities around their schools.

“Many people in the community view this job as a waste of time. They see these children as people who are already wasted. So they see us teachers as wasting our time here, doing nothing.

“That is why I have taken a personal responsibility to educate the community around me — it is my hope that someday these children will be appreciated and not discriminated against. As for me, I am not giving up on them no matter what people’s thoughts are- they are my main motivation.

Since training, I am courageous in talking to people about the benefit of us loving these pupils — or anyone — who is hearing impaired. So they now know that a person with an impairment is just a normal person like them. It has encouraged some of the parents who were hiding their deaf children at home to look for me wherever I am.”

The future relies on teachers

Teachers have the hardest job in the world. But it’s also the most important — the future rests in the hands of people like Chiv, Grace, Josephine and Isabella. They are teaching because they love children and believe in the power of education to let them be all they can be.

VSO is working around the world to help tackle the shortage of quality teachers, and ensure the children in their classes are getting quality — no matter their gender, disability or caste. It’s is also working to ensure that teachers are listened to, nurtured and invested in.