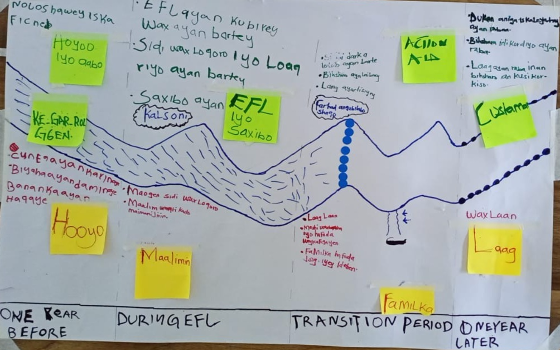

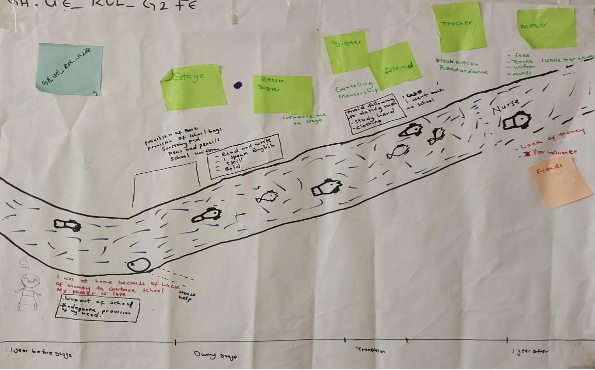

A recent study evaluating the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO)’s Girls’ Education Challenge (GEC) centred around the perspectives of adolescent girls enrolled on Leave No Girl Behind (LNGB) projects. These support education for the most marginalised girls in settings outside of formal school, as well as in their transitions to education and skills or work-related opportunities. The study engaged adolescent girls to understand their perspectives, through participatory ‘Rivers of Life’ and semi-structured interviews across three projects: Education for Life (EfL) in Kenya, Strategic Approaches to Girls’ Education (STAGE) in Ghana and Accelerating Life Skills Literacy and Numeracy of Out of School Adolescent Girls (Aarambha) in Nepal. This blog focuses on the study findings with respect to changes in adolescent girls’ decision-making and future aspirations as a result of their participation in the projects. It also focuses on what more needs to be done to sustain the momentum. All names used in this blog are pseudonyms to protect the identity of all participants interviewed for this study.

Faduma is 21-year-old young woman from Kenya whose family is putting pressure on her to get married. But she wants to focus on her business and has withstood the expectations put on her by family and her community to get married early: “I was told that I will be married to a husband, but I declined…. My family sent the man to talk to me and I told him the truth that I am not ready for marriage and that I just started my business, so I told him to leave me alone.” Faduma is one of several adolescent girls in her community who never attended formal school or who dropped out early, but who the EfL project in Kenya supported in helping learn basic numeracy, literacy and life skills before either enrolling into formal school, vocational skills, or opening a business.

Adolescent girls became more confident to make decisions about their day-to-day lives, but still faced barriers over bigger decisions affecting their futures.

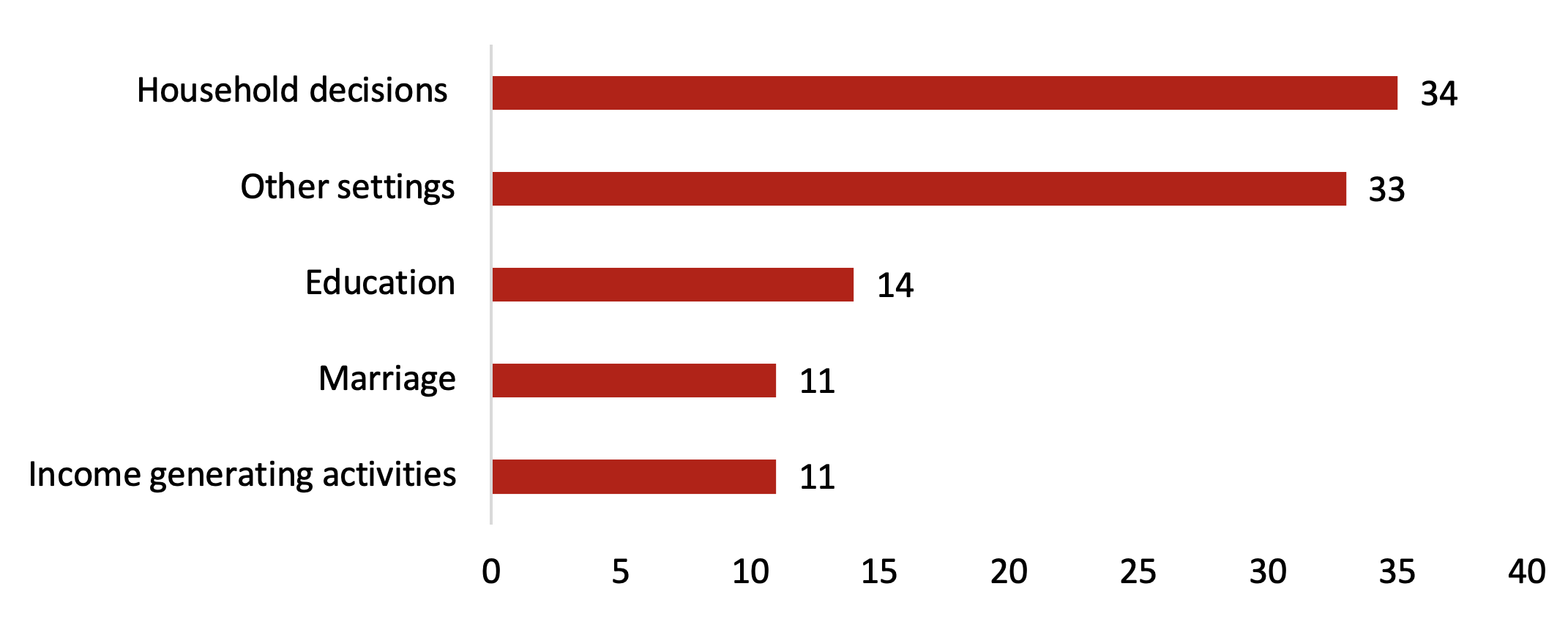

Across the three projects, adolescent girls reported the types of decisions that they now had more say over in relation to their own lives. Around one third reported that they now had more say over day-to-day decisions affecting the household (34 out of 98) or in other settings (33 out of 98). A much smaller number of adolescent girls – such as Faduma – reported that they had greater say over decisions relating to marriage (11 out of 98), and education (14 out of 98).

Many adolescent girls reported how it was the skills that they had gained while attending the LNGB learning centre that helped with them having greater control in decisions. For many, they would be the first in their households to have acquired basic literacy and numeracy skills. 15-year-old Akosua from Ghana tells of how the basic literacy and numeracy skills she acquired meant her parents relied on her more to perform day-to-day tasks: “Now my parents see me as literate. If they are going to make a phone call, they called upon me to come and assist them in identifying the contact number of the person they want to call.”

These basic literacy and numeracy skills were also frequently mentioned by adolescent girls as helping to give them confidence. 18-year-old Chiumbo from Kenya discussed how acquiring these skills while attending the EfL learning centre enabled her to tell her mother what she wanted to do in the future: “I faced my mother and told her that the trainings which I am receiving from the catch-up centre will help me to understand mathematics and one day I will be able to teach others so that they wouldn’t fail in school.”

All LNGB projects provided life skills training. This gave adolescent girls both the types of non-academic skills to help improve their confidence and self-esteem, but also the practical knowledge to know when and how to make decisions which could otherwise traditionally act as barriers to their participation in education. 17-year-old Eleena from Nepal indicated how the content covered in the life skills classes taught her and others the practical skills needed to delay childbirth: “Aarambha taught us about contraceptive methods to not give birth to a child… I did not know anything like that before [and] I learned it after coming to the catch-up learning centre.”

Adolescent girls who transitioned to work-related opportunities reported how the entrepreneurship skills they learned were valued by those around them. This helped elevate their status in households and communities and gave them greater voice in day-to-day decisions. The entrepreneurship skills acquired by 21-year-old Atieno from Kenya elevated her standing in the community, for example, and people who once looked down on her now asked her for business advice: “Before I was seen as someone without any value, the programme came and up to this point is when people have come to know that there is value of the programme.” These types of skills also paved the way for adolescent girls to make themselves more financially independent. According to one female community member in Ghana, for example, girls’ financial independence meant they didn’t “totally rely on their husbands for financial support.”

Participating in the LNGB programmes helped to change the aspirations girls had.

Several adolescent girls discussed how their future aspirations had changed. This was particularly true for those who joined formal schooling after leaving the LNGB learning centre. Of the 33 adolescent girls who transitioned into formal schooling, 15 stated that were it not for the LNGB programme they would now either be engaged in household chores, or some other form of labour. Akwete, a 12-year-old from Ghana who now attends formal school, told us she now aspires to be a nurse: “It is when I joined the [STAGE programme] that I now have a dream of becoming a nurse. They taught us what we can become in future if we are serious with our studies.” Elsewhere, seven adolescent girls who pursued work-related opportunities told us that were it not for the LNGB project they would have been married or become a domestic worker.

Working closely with communities was important to help shift gender norms, and so allow adolescent girls to exercise their voice over decisions relating to them.

It is not enough to focus on empowering adolescent girls to have a greater say in decisions that directly affect them. This needs to go hand-in-hand with also addressing the gender social norms which often prevent them from having a say over their lives – without a focus on this, girls can be left vulnerable to risk of retribution. LNGB projects did this by embedding community sensitisation campaigns into the design to help create conditions needed to address negative gender social norms.

There are many examples of success. Aarambha in Nepal, for example, worked with Change Champions. These were influential and well-respected members of the communities (e.g. religious leaders) who worked with community members and households to try and change mindsets surrounding harmful practices like early marriage. One discussion with female community members discussed the programme’s positive role in sensitising them to the benefits of delaying marriage: “Only after Aarambha came, we got to know that marriage should be done only after the age of 20 years old. By learning that I used to take my daughter-in-law's child in my lap and I used to send my daughter-in-law to study.” Seeing what adolescent girls were capable of, helped in shifting once-negative family and community attitudes towards them.

Changing gender social norms to enable the conditions needed to elevate the voices of adolescent girls in decisions relating to their lives is not a short-term fix.

For truly transformative change, long-term support and engagement is required, both to offer continued support to girls as well working to shift the attitudes needed for sustainable change. In terms of shifting attitudes, this support must span well beyond the timeframe of specific projects. Otherwise, as the study found, adolescent girls supported by the projects, who have at last been able to express their voice, can be at risk of harm. 14-year-old Noor from Nepal, for example, expressed her wishes to her parents to continue attending school after completing at the Aarambha learning centre. However, her father was against the idea now that she is older and of a marriageable age and so she now attends school in secret when her father is away in the city working. Male community members in Kenya also expressed how adolescent girls’ new-found financial independence has contributed to tensions in households, which had left them at the threat of physical violence: “There was conflict in some families because of that money [that girls earnt]. Some husbands broke the sewing machines because the wives were uncontrollable.”

Lessons for the future

The findings from the study offer valuable lessons for the design of any education programmes aimed at supporting education for the most marginalised out-of-school adolescent girls.

- It is important to continue supporting adolescent girls beyond the education programme itself, to progress back into formal schooling or on to skills- or-work-related pathways.

- It is important to give them options about their transition pathways and vocations (including non-traditional vocations), such as through life skills training and other assistance that gives them the confidence to choose.

- It requires sustained engagement with community stakeholders to help shift gender social norms which negatively affect girls’ participation in education and work-related opportunities.

- Real, transformative and sustained change requires a longer-term political commitment to the most marginalised adolescent girls beyond the end of the project lifespan.